Our friend Trevor Barton is stopping by with a guest review for Autonomous, by Annalee Newitz.

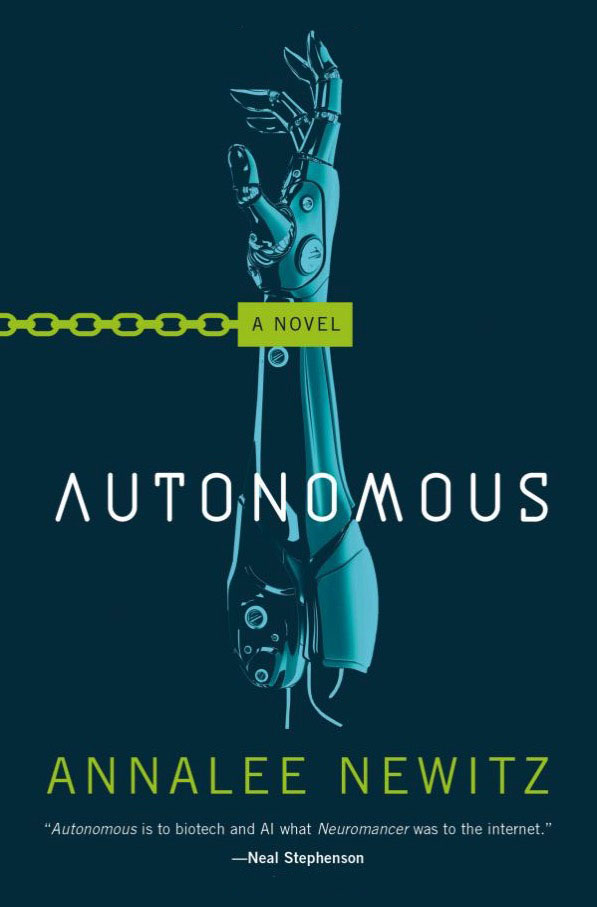

Title: Autonomous*

Author: Annalee Newitz

Genre: Science Fiction / Cyberpunk

LGBTQ+ Category: Several

Publisher: Orbit

Pages: 304

Blurb: Earth, 2144. Jack is an anti-patent scientist turned drug pirate, traversing the world in a submarine as a pharmaceutical Robin Hood, fabricating cheap medicines for those who can’t otherwise afford them. But her latest drug hack has left a trail of lethal overdoses as people become addicted to their work, doing repetitive tasks until they become unsafe or insane.

Hot on her trail is an unlikely pair: Eliasz, a brooding military agent, and his indentured robotic partner, Paladin. As they race to stop information about the sinister origins of Jack’s drug from getting out, they begin to form an uncommonly close bond that neither of them fully understands.

And underlying it all is one fundamental question: is freedom possible in a culture where everything, even people, can be owned?

Review by Trevor

This month, Annalee Newitz (of Gizmodo and Ars Technica fame won a Lambda Literary LGBTQ SF award for her 2017 book “Autonomous”. This got me intrigued, so I spent part of a recent week out to buy and read a copy. Here are some of my reflections (opinions my own).

Autonomous has a rich and original world and an important message to give about the inhumanity of large organisations when driven by capitalist greed alone. It’s a queer science fiction must-read, and possibly a master work in the making. If you like to punk up your SF you’ll certainly love the well-read world Newitz creates. It’s a Gibson/PKD type place filled with the body-hacked and the glitchy; a place short circuiting the bio and the cyber together in a new flavour.

The title, of course, is suggestive of the robotic (automaton, automated, automatic) as well as of someone or some thing with agency (AI, free will, philosophy of mind, non-programmatic functioning). But, with nods to those elements, ultimately it’s use here is political and about personal freedoms. There’s the robot character Paladin’s degrees of autonomy of thought and action; there’s protagonist Jack the pirate/scientist’s moral freedom from the corporate/industrial machine. Then there are Eliasz’s failed freedoms (his suggested combat stress locking him into a certain mental view of the world, his struggles to express himself sexually). One has to also note Threezed’s freedom from slavery; and of course, most centrally to the plot, Society’s collective self-determination and, in relation to that, individual free will in a world where businesses can manipulate fundamentals of health and wellbeing to serve their own ends.

What this all creates is something more nuanced than a diatribe about the robotisation of human society or the marvel of an AI coming into being (subjects that, frankly these days, would be a bit of a yawn on their own). It’s instead a politically-satirical word of caution about the place of tech and science in relation to our evermore encroaching corporatism – and what that might mean in the future.

In as much as any speculative fiction writing is also serious futurology, and humbly, I think Newitz is right about this: to think automation and AI are the threats to fear most in coming decades is simplistic at best. It feels poignant and real to suggest otherwise and Newitz makes her case (reads her future) convincingly.

It’s time. It’s time for us to have more fiction exploring human-like artificial intelligence told from the perspective of that intelligence rather than our own. It’s time for that to be done in three dimensional ways that don’t necessarily stick within the tired old robot memes. (I adore Paladin’s exploration of gender identity, of private fancies and how to embellish them to make them better, of efforts to untangle how much love is of her own desiring and how much is programmatic.) It’s time to explore the always-already queerness of the robotic. It’s time to have some technosexuality and deal with it frankly. It’s time to step past the “evil AI” trope and ask ourselves where evil comes from. It’s a time for political satire (and, if it were permissible, which it isn’t, I’d add some lovely quotes from “Autonomous” here about big pharma and open access scientific publishing); and, of course, it’s definitely time to queery science fiction.

I would say that? Well, OK; but that doesn’t weaken my point does it? So, yeah! Go Newitz and go LAMBDA! In fact, isn’t it refreshing to have some hard-nosed biopunk be a winner? That feels to me like affirmation that work can be regarded as a serious genre contribution or as literary whilst still having accessible non-poetic language. Fab!

Job done. Review over.

But wait. There’s one more thing I can’t let go of. It isn’t a big thing (and you could almost brush past it in the book).

We need to talk about Eliasz.

I admit that as a gay male author reading, I did blink (rather than gaze) at him. He’s probably the only main cis male character who self-defines as heterosexual clearly and one can’t help feeling that, because of this, he’s kind of held up as this unrefined, unreconstructed, un-evolved soldier closing down on alternatives open to him such as coming out as gay (enough backstory implies some plausibility to this option) or at least coming out as (permitting himself to be honest with himself as) technosexual.

Instead his sexual partner seems to make the journey: from defining as male to defining as a female who still gets addressed as the same ‘buddy’ (suggesting, to me at least, male) and from hoping for an objective love to settling for a persistent anthropomorphism. One is left wondering how much this choice is because she fears losing Eliasz if she doesn’t make that transition. It certainly weaves in another way of looking at freedoms for both characters, but to me it is problematic (Eliasz “who’s da man” is the only main character who can’t, or doesn’t, evolve. Even readers who are OK with the fact that his partner’s transition is through self-definition alone may pause to look at why she elects to make that change because it’s in response to Eliasz’s projection – an act for him and not for herself; an act based on his self-centredness perhaps).

I say I blinked. I didn’t cough. Eliasz does get his HEA and you could call all this just queer sci fi perfection. We’ve got the hyper-masculine and the homoerotic doing their natural bonk into each other and deconsructing them is such easy pickings: to queery SF is also, surely, to queery the military/industrial/heteronormative dominating the genre in this way such that (if one wants to be a real punk about it) that’s the thing that ends up getting left in tatters rocking gently in the corner rather than being celebrated jerking off over big phallic guns but never (shock! horror!) in a gay way (perish the thought!). So, OK. Eliasz has to be in trouble for that to work. The body corporate has been dealt a blow and so, as the tail side of the same coin, the body masculine and military must be too.

But does it work for the character? Well, yes. His version of his lover is made up: a construct of his own imagining and so he excludes the real her. His sense of self actively excludes too in as much as he fails to be honest with himself, his health, his desires. A story told from the angle of the queer, the punk, the radical can’t include exclusive things and so, if a character’s expression of masculinity relies on exclusion in order to exist then surely it should be queried.

I’m fascinated that Eliasz is ultimately too closed down to listen to Jack, meaning a fleeting chance (lasting seconds) to change trajectory and step up as a (even the?) true hero (masculine without the toxicity) gets ignored in a way that’s believable for who Eliasz is as a person. Yeah, that… uh, gosh… reminds me of some real men I’ve known.

Trevor Barton is the author of the Brobots trilogy. He lives in the EU with his husbear.