Gomen nasai!

I’m Jim Comer and I read, edit, and post on QueerSF. This is the third of an irregular series of dispatches from the front: I read very widely across the fields of history, science, language and religion, and want to make sure that the QUILTBAGs back home are suitably informed. For writers and readers, here is the third in a series of book reviews, on tales of same-sex love (“nanshoku”) in Japan. I hope that you enjoy it.

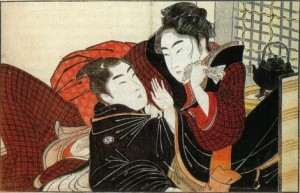

Reflections on The Great Mirror of Male Love, by Ihara Saikaku

J. Comer

Reading a text from another place, and from another time always challenges the reader. When the text brings with it a different set of questions about the nature of the world and human beings, or when it brings different answers, the reader must try to absorb this text, soak in its worldview and its assumptions. When the text, in addition to these features, challenges a taboo which we hold dear, then the reader may find the experience bitter– or savory. While reading Ihara Saikaku’s classic The Great Mirror of Male Love, a book of forty short stories (published 1687) about love between men, boys, and women, the reader may find the experience a strange one, and only by the most thoughtful and careful reading can they appreciate all that is to be found in this message (for so it is) from another world. (Many readers may have heard of the book through the anime Samurai Champloo in which the Dutchman Isaac Kitching had read The Great Mirror and come to Japan to seek a male lover.)

Saikaku was an eighteenth-century Japanese male author. He was the first author in Japanese history to support himself entirely through the work of his brush: that is, he didn’t have another job in addition to being a writer. (For the curious, Washington Irving was the American equivalent.) He wrote a great deal of erotic literature in addition to The Great Mirror, with The Life of An Amorous Woman being one of his most often-cited works. It might surprise Americans, heirs to the Puritan tradition, to learn that the first professional writer in Japan brushed out stories of brothels and boy streetwalkers, but Buddhism, the dominant creed of the land, did not frown on commercial sex or on sex between men in the same ways that the mid-eastern monotheisms have done. Japan, for example, has never had ‘sodomy laws’ of the European and American sort, though same-sex marriage doesn’t exist there. Therefore, Saikaku was freer to follow an age-old dictate. Sex sells. And in a society without significant taboos on the topic, love between men and boys was common and uncontroversial.

Now. The reader is likely to be wondering exactly how seamy this book is, and how lewd this review is going to be. First of all, no one on QSF endorses sex between adults and minors, and no support for this idea is here. The author (me) doesn’t want the age of consent to change, and doesn’t think that there is any need for it in our society. We don’t need a culture of commercial man-boy sex in the United States, and our society would not be improved by it. (Case in point? Thailand.)

Second of all, Saikaku may be a cicerone, but he isn’t a pornographer. While there are allusions to and statements of love and sex happening between assorted couples, there is no explicit description of genitals or of sexual positions, and the stories are really about love, and not sex.

One of the most striking things about The Great Mirror, at least to me, is that it presents not only a clear vision of a world in which same-sex love is taken completely for granted without women being secluded in harems or gynecaea, but also a clear vision of a world in which intergenerational love is both bought and sold, and entered into freely. Scholarly interpretations of Greco-Roman pederasty have alternated between frantic denial and creative if wilfull misreading of the available texts, with James Davidson’s books being the clearest exploration of the material in my opinion. And the huge genre of male-male love poetry and love tales in Arabic and Persian always had the out that the manly love in question was not physical, with Islam’s harsh punishment for liwayat (sodomy) being the probable reason. But no such disavowal is possible here. It’s abundantly clear that men loved boys, both emotionally and carnally; that men loved men, likewise, and that boys, whether or not they were being exploited and whether or not they were being paid, had both the right to refuse and the capacity for affection shared with other males. Nor was any of this incompatible with marriage– indeed, some stories deal with male-female love, including cross-dressing (on one occasion, a male actor who plays female roles falls in love with a lady, enters her home in drag, is taken for sex by the husband, who discovers that this ‘woman’ is male, and the two males have sex! Some tales are so weird to modern readers that it’s necessary to reread them in order to avoid confusion, and some are so powerful emotionally as to reward rereading. (On talking to a friend who knew Japanese love stories, the reviewer found out that Saikaku’s Five Women Who Loved Love also dealt with same-sex as well as opposite-sex love, with the happiest of the five amorous ladies being she who turned a boy-loving samurai toward male-female love!)

So, having set down what the book is not, the reviewer probably needs to tell the readers what it is. The book (a best-seller when released) is divided into two sections, each comprising a series of chapters and stories. The setting is Japan during the Edo period, roughly contemporary with the author. Fans of such works as Chushingura/Forty-Seven Ronin, Lone Wolf and Cub, and Blade of the Immortal will find much that is familiar here and many may appreciate this writer merely for the quality of the stories. The first group of stories are mostly about samurai and their romantic relationships with pages and monks. The second section largely deals with the boy actors who played women in the kabuki theater, and the older townsmen, merchants and so on who paid them for their company. This section also includes some opposite-sex love tales. Each of the stories is fairly short and the book is a quick enough read. The landscapes and cities of Japan are vividly described, with bamb0o-bark raincoats, paintings on fans, forests and seas, mushroom-picking parties, dry riverbeds at night with the sparks of firefly light and oil lamps. The author takes a very affected, opinionated voice when discussing gender, and constantly editorializes on why males are more desirable than women in a way that is both funny and disturbing.

So, when we read so profoundly alien a work, what reactions do we experience? The reviewer would like to mention three reactions. The first was shock. The narrator explains that there are two types of men (under discussion): men who are married, and consort with boys on the side, and men who ‘hate women’ and love only other males. This doesn’t map onto modern concepts of genetic or environmental explanations for LGBT status, and it doesn’t conform to our categories either. The stories are shocking, also, for their Japanese assumption that attachment leads to suffering: lovers are separated, die by their own swords, die by the hands of others, become Buddhist monks (a startling number of times) and are otherwise parted. Why? Because Saikaku knew perfectly well that an adolescent male was not going to spend the rest of his life with an older man who fancied him. Men did not, after all, marry boys in Japan, and still don’t (Japan does not have marriage equality, and much of the energy that went into achieving it in the US is spent by Japanese womens’ groups on resisting arranged marriages and helping raise the status of women). And the boy would eventually become a man, (as in “Visiting From Edo”) and lose his boyish good looks. Parting was inevitable, and the question was how it would happen, and when. In some stories (such as “Aloeswood Boy of the East”), the boy and his admirer end up together, but the shortness of the stories means that we learn little more. Couples who lived together for their whole lives, such Han’emon and Mondo (in “Two Old Cherry Trees”), were rare. The cringe-worthy custom of cutting or biting off one’s fingers in order to prove the love one felt for someone is also a source of shock (as in “Nightingale in the Snow”, “An Onnagata’s Tosa Diary”, and “Nails Hammered into an Amateur Painting”), and when shame leads to seppuku, such as in “They Waited Three Years To Die”, the reader is again, somewhat horrified.

The second reaction, if the reader decides to go on, is alienation. The world of Edo-period Japan, a nation almost entirely cut off from outside contact save through Dutch trade to Nagasaki, is foreign to most readers, but segment of it society consisting of “conoisseurs of boy love”, as they are frankly called at one point, is weirder still to those of us who grew up in Western nations, who form the majority of QSF’s readers and writers. What are we to make of a setting where people use tooth powder, tattoo themselves with their lovers’ names, and read printed books, but fight duels with swords and travel on foot? On one page, a soldier weeps into his sleeves because a boy refused him; elsewhere, actors who dress in womens’ clothing (there were no actresses) sell toothpicks engraved with their (heraldic) crests as souvenirs. Men fall in love with women, and a wife comes to a boy’s home to beg, since her husband (!) has spent all he owns on the boy and is dying of grief. Dolls talk (and fall in love) and lovers plan to visit in the next life, since falling in love can be for many lifetimes. In short, the setting is a world much stranger to us than most science fiction.

The honest answer to such a reaction is that short of reading a great deal of Japanese cultural history, there is no way to explain all of this complexity. Even with extensive notes and a nicely done introduction, this translation cannot fully bridge the gap between the Edo ‘floating world’ and our own. The reviewer has read The Tale of Genji and The Tales of Ise, as well as other Japanese classics, but the sheer volume of references and allusions to Japanese, Chinese and Indian history, religion, and culture overwhelm the reader. And what are we to make of the supernatural references which occur? It’s hard to know what to make of all this.

The final reaction is comprehension, of a sort. The reader can recognize the pain of Sanzaburo and the nameless ronin in “The Man Who Resented Another’s Shouts”. When the actor Hayanojo ends up penniless as his beauty fades, and kills himself, we’re led to contemplate how all of us age and how fickle human beings (gay or straight) can be. And when, in “Bamboo Clappers Strike the Hateful Number”, we are led through magic to realize that the ‘boy’ actors lie about their ages, we can laugh wryly with the monk and his guests. Dishonesty, jealousy, and grief are human, and transcend culture and language. In all its forms, so does love.

What is the significance, in the long term, of The Great Mirror, and other works of same-sex romance and erotica? We can read these stories simply as literature, and be entertained by a glimpse into another place and time. We can read them as texts from a wholly different construction of sexuality, and learn of a world whose bigotries and taboos were not our own–not a paradise of uninhibited man-to-man sex, but simply another world. We can be moved by the sadness and sometimes, by the joy of the lovers whose symbol is the swift-fading cherry bloom.

Recommended for anyone fascinated by Asian culture, of course, and as a useful example of *unused* furniture.