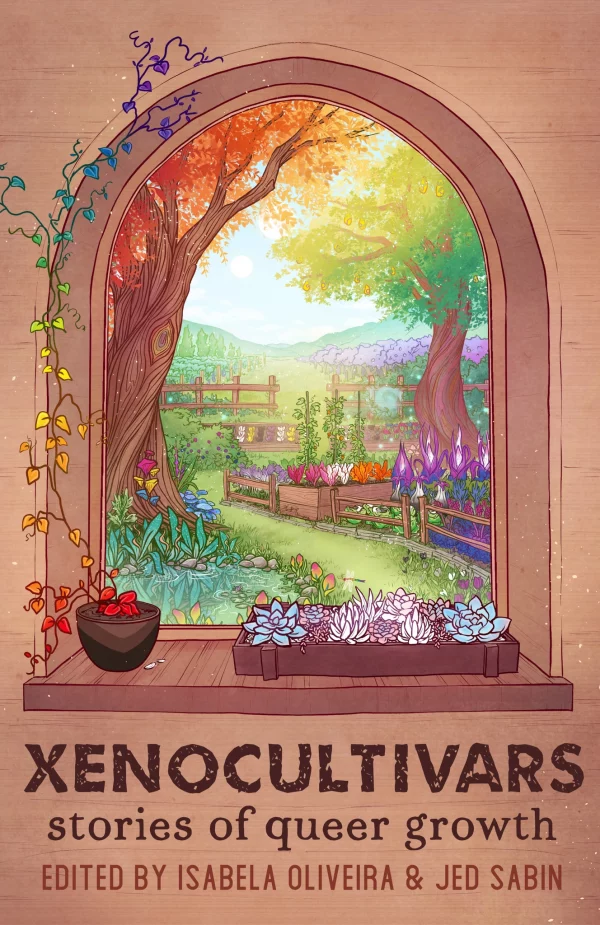

Speculatively Queer has a new queer spec fic anthology out (bi, gay, intersex, lesbian, non-binary, poly, trans): Xenocultivars: Stories of Queer Growth.

This collection of speculative short fiction is about all kinds of queer growth, from emerging and developing to flourishing and cultivating. Whether they’re tender sprouts just beginning to discover themselves or deeply rooted leaders fiercely defending those they love, the people in these stories have this in common: you can’t tell them what to do. They grow as they please.

Content Notes: ableism, abuse, animal harm, anxiety, (offscreen) attempted assassination/murder, blood, body horror, bullying, child abandonment, (offscreen non-graphic) death, depression, difficulty with accepting disability, explosion, (references to) fatphobia, food insecurity, grieving for a parent, (references to) homophobia, illness and recovery, injury, life-threatening corporate negligence, missing child, mortal peril, sex, (reference to) self-harm, substance use, threat of violence, transphobia, war

Publisher eBook | Publisher Paperback | B&N | Kobo

Excerpt

The Thing About the Jack-o’-Lanterns

by Maggie Damken

“Remember,” my grandmother used to say, “you cannot give something a mouth and expect it to be silent.” Then she would leave me to carve the pumpkins in peace.

While the light of the evening news painted her blue and white in the next room, I hollowed out two jack-o’-lanterns with a knife too big for my little hands. “You can handle it by yourself, can’t you?” Grandma suggested, and I rose readily to the occasion of keeping yet another secret with her. The depth of our relationship was based on things we didn’t tell my mom: I didn’t snitch when she started smoking again, and she kept to herself all the trouble I had with the other girls at school. Back and forth, a secret for a secret — every item added to the list strengthened our camaraderie until we could communicate in half-nods and winks, the language of cutthroats and thieves.

Once I finished with the pumpkins, I lit candles inside their bodies and pressed my ear close to the rictus I’d gifted them. If seashells carry the sound of the ocean inside them, no matter how far from shore, then pumpkins carry the rattle of the boneyard. I can’t believe you have my eyes, said a man’s thin, reedy voice, carried on the candle’s coil of smoke. After all this time!

Over the years, as I grew up, I started to understand why Grandma never joined me or even pressed a curious ear to the pumpkins I carved. Your mother is too hard on you, don’t listen to her was a message that comforted me as a teen, but it was about the only one that made any sense. Turn to the purple dawn and begin your journey there, one spirit offered, while another advised, The joy of the moon is the envy of the sun. Ghosts, I learned, were allowed to be cryptic and strange, and owed no one — not even their descendants — common-sense explanations. Why pay attention to messages that meant less than the platitudes tucked inside fortune cookies? Sometimes I wished I were like Grandma, that I could ignore a tradition simply because none of it made sense, but every year I ended up in her kitchen creating a conduit. When I imagined the ghosts looking forward to it, I felt too guilty to deny them, even though I couldn’t comprehend them.

I wished I were a ghost. Maybe then I wouldn’t spend every day of my life explaining myself, twisting inside and out to make sense of who I was, all while keeping some things close to avoid having to explain them at all. Mom kept needling me about why I never had a boyfriend, how could I get all the way through college without even wanting a boyfriend — and when Grandma’s cigarettes finally put her underground, I didn’t have anyone to deflect the constant barrage of serrated questions, each one trying to carve my life into a mask with features my mother could understand.

I considered forgoing tradition that autumn. I could tell myself, with some success, that I was too old for it. I could tell myself, with much more success, that I didn’t want to hear my sharp, straightforward Grandma rendered obscure and nonsensical in death.

But there was one more secret I wanted to tell her, something I’d buried down at the root of me, a fruit I was finally ready to cut free of its vines.

So I bought a pumpkin that was flecked with green, covered in warts — triumphant in its ugliness, the kind of choice I used to make when Grandma took me to the pumpkin patch. The ugliest ones, I always felt, made the best conduits. Spoonful by spoonful, I scooped out its guts. With a Sharpie I marked where its shocked eyes would be, its triangular nose, its smile composed of a hundred jagged knives, and I incised away the flesh. After I lit the candle inside it, I pressed my ear close to its mouth, and listened for the skeletal gasp that meant someone had accepted my invitation. It happened within seconds.

Then I told her.

That the names the girls called me on the playground, while coarse and cruel, were not incorrect. That it broke my heart when my best friend started dating not because she spent less time with me, but because she hadn’t picked me. That the first time I kissed a woman I felt my soul slam back into my body. It made me feel like Cinderella: transformed, elevated, suddenly what and where I was meant to be, even if I had to leave for home by midnight.

For a long time my grandmother didn’t say anything, and my stomach tightened with knots as I considered that perhaps I hadn’t been speaking to her at all, but to someone else who wouldn’t understand the gravity of my declaration. Or maybe I had well and truly lost her this time, a loss more final than death.

Then she exhaled candle smoke against my ear in a focused, steady stream, the same way she used to blow cigarette smoke. Oh, kid, she said, in a voice that was still her own, deep and rich and low. If I could have married a woman when I was young, you can bet your ass I would have.

And suddenly there were other spirits, too, who had never before come to visit me, rising in a clamoring chorus for a turn with the pumpkin’s mouth, to make sure I knew — even in nonsense terms — that I was only the most recent fruit on the sprawling vine of our family’s patch, and I had never, not for an instant, been alone.

Editor Bios

Speculatively Queer is a small press in the Pacific Northwest publishing stories about queer hope, joy, love, affirmation, and community. SQ has released two anthologies, It Gets Even Better: Stories of Queer Possibility and Xenocultivars: Stories of Queer Growth.

Isabela Oliveira has been a professional editor for years, from technical documents to pop culture content. While attending college, she kept busy as the poetry editor and later the editor-in-chief of her university’s literary journal, the Salmon Creek Journal. Isabela started speaking on panels at fan conventions in 2016 and has been at it ever since. These days, she’s working as an editor by day, and an occasional podcast co-host, a crafter and maker, and an aspiring voice actress in her free time.

Jed Sabin is a jack-of-all-trades with professional experience as an editor, writer, scientist, project coordinator, and logistics manager. They were editor-in-chief of their college student newspaper, and they worked as an editor on the Maze of Games puzzle novel. Their writing has been published by Daily Science Fiction and Wired Magazine. Their hobbies include playing hockey, inventing weird cocktails, and maintaining a spreadsheet of over 600 queer movies.