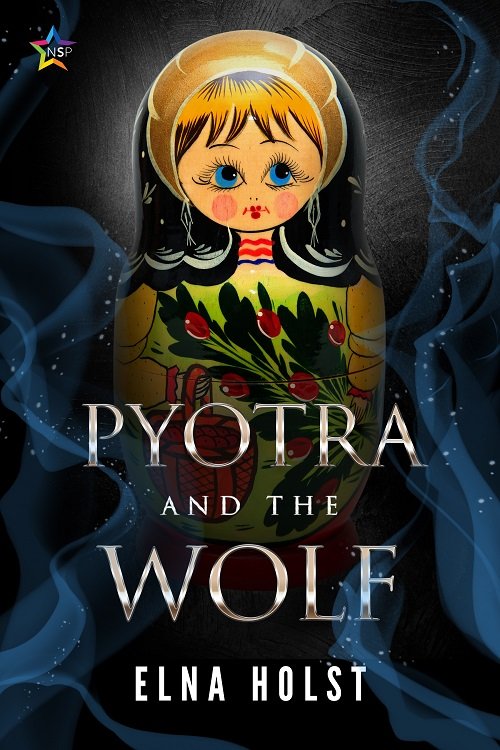

Elna Holst has a new FF Paranormal book out: Pyotra and the Wolf. And there’s a giveaway.

For the space of a breath or two, that wolf had entranced her, mesmerised her, made her believe—the impossible. And that was all it took.

Nothing about this wolf was as it should be.

Pyotra Nikolayevna Kulakova lives in a small Russian settlement in the northern Siberian taiga, where the polar night lasts for a good month out of the year and the temperature rarely reaches above freezing point. Pyotra’s days, too, seem congealed and unchanging, laden with grief, until her baby brother’s close encounter with a tundra wolf upends the lives of the three members of the Kulakov family in one fell swoop.

Pyotra and the Wolf is a queer retelling of Sergei Prokofiev’s symphonic fairy tale, structurally influenced by matryoshka dolls and memory castles. This is a story of darkness and light, love and loss, beast and human. Whichever way the spinning kopek falls.

Giveaway

One lucky winner will receive a $10.00 NineStar Press Gift Code!

Direct Link: http://www.rafflecopter.com/rafl/display/555033ec890/?widget_template=589504cd4f3bedde0b6e64c2

Excerpt

On the day that was to change the lives of the three remaining members of the Kulakov family forever, it was night. Pyotra Nikolayevna Kulakova lived with her grandfather and younger brother outside a minuscule Russian settlement in the northern Siberian snow forest, where the polar night lasts for a good month out of the year. According to the unsmiling face of the clock on the wall on Boris Ilyich’s izba, however, it was in the early hours of the morning that Pyotra pushed her weight against the door, caught between the dread of the freezing cold without and staying trapped inside, unable to procure sustenance for the two men under her care.

Her brother, it might be argued, was too young to be called a man, and her dedushka was worn and grey, an old curmudgeon who had lost his eyesight, if not his wits. Pyotra loved them dearly, desperately, with the parentless child’s determination to cling to what has been left her. Boris, in turn, doted upon his grandchildren: Pyotra, the twenty-two-year-old, and Sergei, nearly twelve. Not that he ever told them as much. It was not his way.

Pyotra sighed as the door refused to budge. A metre of snow had fallen while they slept. “Come help me, duckling, if you want to see the sun again.”

Sergei made a noise through his nose. He sat by the fireplace, fiddling with his tackle, oiling his rod, making sure the lines were not tangled. It was a new favourite pastime of his. Lately, he had taken it into his head that he was to be the future provider of the family. Pyotra assumed it was a notion he had picked up at the village school. Their father had never been much of a provider; he had made sure he had his vodka, and that was that. Sergei was too young to remember.

“There won’t be any sun for another week or so,” he replied, holding his rod up for inspection. “And stop calling me ‘duck.’”

Pyotra hid a smile. She was by no means ready to let go of her private memory of Sergei taking his first waddling steps towards her, as their mother, Serafima, gasped, “Look, look who’s walking. My little duck!”

It was all that Serafima Anatoliyevna had left her offspring; that and her grey-blue eyes, her peculiar-coloured curls, and her steely resolve to survive, to thrive, even in the most austere and unforgiving corner of the world.

Except, she hadn’t. She had walked out into the Arctic night, only to be brought back by a search party a few days later. Parts of her, at least. Bones, hair, ravaged flesh, the gold wedding band by which she had been identified. Attacked by a pack of wolves was the universal verdict. Their father could not cope, it was likewise said; he drowned his sorrows in liquid comfort and went down with it.

And then they were three.

Pyotra Nikolayevna had never been able to forgive her parents for dying. But she could not give up on their little duck, bright-eyed and pink-faced, holding his chubby arms out to her as if she was the centre and epitome of existence.

His arms were not that chubby any more, but still.

At the table, Boris moved uneasily, his unseeing eyes directed towards the unflinching darkness of their one grimy window to the outside world.

“Let it be, Pyotrushka,” he burred, winding his fingers through his beard. “There’s an ill wind blowing. It smells like…wolf.”

Pyotra clicked her tongue. Shaking her head at her grandfather would be a waste of energy better employed in breaking out of the snowed-in log cabin. “For pity’s sake, Ded. This isn’t the nineteenth century, nor even the twentieth. The weather holds no omens to be deciphered. If you smell something off, it’s probably Sergei.”

“Ey!” Her brother looked up at her for the first time, adorably affronted.

Pyotra winked at him and turned to give the door another mighty shove. It cracked open a centimetre or two, a small avalanche of fresh snow tumbling in through the opening.

“Bring me the spade and the bucket, duck,” she called over her shoulder to Sergei, her tone of voice forestalling opposition.

As she started shovelling, clearing a passage out at less than a snail’s pace across a rugged cliff, Pyotra Kulakova sighed anew. This was going to be one long day, irrespective of the lack of sunlight.

#

It was past noon before Pyotra and Sergei—who eventually grew bored with his own resistance—had managed to come as far as to the communal road leading down to the village, which had been cleared by the local snow removal team. Pyotra took one look at Sergei’s blanched face and sent him back to fill up the samovar for Boris, while she proceeded down to the one shop within an eighty-kilometre radius.

“I will be back in a couple of hours,” she told him, pinching some warmth into his cheeks. “Don’t do anything stupid, please.”

“I’m not the stupid one.” Sergei stuck out his tongue and batted her hands away. “That hurts!”

“Not as much as frostbite, let me tell you. Or better yet, let Dedushka tell you. That’ll keep you both occupied.”

With a rude sign—another new trick they had that eminent educational institution to thank for—Sergei ran back to the alluring warmth of the hearth. Watching him go, Pyotra felt a sting of loneliness. Of loneliness, but also of the constant worry that came over her whenever she had to leave him, leave them both. Since her father’s earthly remains had been lowered into the ground to join her mother’s, two years after their first, gut-wrenching loss, Pyotra Nikolayevna had lived with a droning terror at the back of her mind, which she hadn’t any better name for than Things Could Happen. The namelessness of it only served to magnify her dread.

Shaking herself, Pyotra straightened her headband torch, hiked her empty rucksack higher onto her shoulders, and set off.

Author Bio

Often quirky, always queer, Elna Holst is an unapologetic genre-bender who writes anything from stories of sapphic lust and love to the odd existentialist horror piece, reads Tolstoy, and plays contract bridge. Find her on Instagram or Goodreads.