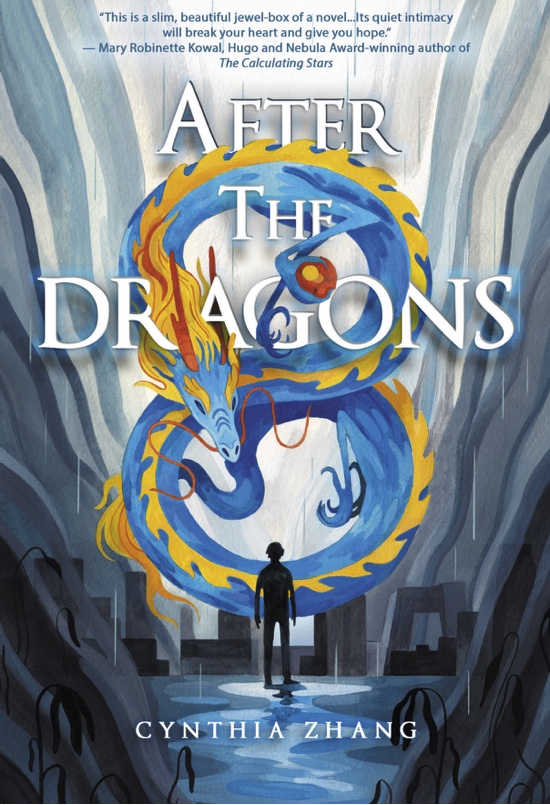

Cynthia Zhang has a new gay sci fantasy romance out: After the Dragons.

Dragons were fire and terror to the Western world, but in the East they brought life-giving rain…

Now, no longer hailed as gods and struggling in the overheated pollution of Beijing, only the Eastern dragons survive. As drought plagues the aquatic creatures, a mysterious disease—shaolong, or “burnt lung”—afflicts the city’s human inhabitants.

Jaded college student Xiang Kaifei scours Beijing streets for abandoned dragons, distracting himself from his diagnosis. Elijah Ahmed, a biracial American medical researcher, is drawn to Beijing by the memory of his grandmother and her death by shaolong. Interest in Beijing’s dragons leads Kai and Eli into an unlikely partnership. With the resources of Kai’s dragon rescue and Eli’s immunology research, can the pair find a cure for shaolong and safety for the dragons? Eli and Kai must confront old ghosts and hard truths if there is any hope for themselves or the dragons they love.

Warning: terminal illness (though the character does not die in the book and hope is maintained that there will be a cure)

Get It At Amazon | Publisher | B&N | Kobo

Excerpt

The courtyard between the shops where Eli and Kai stand is not large. It’s a space designated for respite and not activity; crammed with spectators and bettors, it feels even smaller, air thick with the scent of beer and smoke and bodies pressed in uncomfortable proximity. Men crowd the white-chalked circles of the individual rings, screaming vitriol and encouragement by turns. Outside the rings, thin-lipped trainers sit cross-legged and hunched forward, nearly motionless but for the laconic hand motions and whistles which direct their dragons this way or that. Inside the rings, hissing dragons face each other, weighted jesses around their back legs preventing them from flying more than a few meters. Plastic caps have been placed over claws and leather guards cover vulnerable stomachs and throats. Even with such protections the matches are fierce, the dragons diving at each other and wrestling in the dirt as they try to force their opponent to either step outside the ring or yield in a belly-up surrender. Each time a dragon succeeds, a wave of cheers and groans erupts from the spectators. Employees from the surrounding stores circle the crowds, alternatively hawking bottles of beer and smoking as they observe the fights. At one end of the courtyard, opposite the archway through which visitors stream in out of the streets, Mr. Lin sits on a plastic lawn chair, a white T-shirted emperor with his referee whistle and yellow legal pad. Dr. Wang stands beside him, an enthusiastic interloper in her polo shirt and pressed slacks.

“So there it is,” Kai says, nodding over his sketchbook at the crowd from where they’re standing, close enough so that Kai can nominally monitor the fights while far enough away that they can comfortably talk. “Five thousand years of civilization.”

“Ah,” Eli says, uncertain how to respond. Kai’s voice is flippant, but his eyes, as they watch the circles of drunk men, are sharp. Eli knows that dragon fighting has a long history in China, a codified emperor’s sport more than anything, but he knows that it’s always been controversial. Critics compare it to bear baiting and bull fights, other instances of animal suffering for the sake of human entertainment; defenders cite the natural behavior of dragons in the wild and argue that, when correct procedures are followed, the fights provide young dragons a much-needed outlet for otherwise destructive instincts. In lieu of a definitive verdict, the sport is highly regulated, traditional leather armor and claw guards now mandatory, and elaborate new scoring rules have been put in place to minimize injury. But armor slips and plastic breaks and even without evisceration, bruised ribs and broken bones are serious injuries. American-raised and acutely conscious of his country’s own history of moral imperialism, its quintessentially American strategy of saving countries by bombing them, Eli tries to avoid casting cultural judgment. There are few things worse to him than being that tourist cliché, the outraged Westerner speaking out against a cultural practice they barely know anything about. But in the face of Kai’s obvious outrage, he wonders if there is something hypocritical about the ease with which he brushes away the faint revulsion dragon fighting has always invoked in him.

There’s a sketchbook open in front of Kai, but he only glances at it periodically, occasionally erasing a mark here or adding a few tentative lines there. When he tilts his head, they almost coalesce into something, but then Eli blinks and it’s gone.

“What are you working on?” Eli asks.

“This?” Kai looks up, face half-shadowed in the artificial light. “It’s not — well, it actually isn’t anything yet. One of my professors used to talk about feeling in art, the way abstract artists could use a few strokes of line and color to convey

emotion. I’m trying that, I guess. Getting down a mood without worrying about representing anything. Being avant-garde,” he says, the last word accompanied with an eye-roll and heavy French accent.

“Très bon,” Eli says, shifting so he can better peer at the sketches. “You’re an art student, then?”

“Biology,” Kai says, idly darkening a few lines in a corner. “Art students don’t get paid. It helps with the anatomy, though. You’re either chemistry or biology, I’m guessing?”

“Both, actually. Technically just graduated, so I guess I’m not a student anymore either,” Eli says, rubbing the back of his neck. “This is sort of like a vacation before I focus on med school applications.”

“A vacation where you do research?”

“I didn’t want to be completely idle, I guess,” Eli says, shrugging. “Might as well try to do something good with all this new free time.”

“Eli, Xiao Kai!” Dr. Wang calls. Mr. Lin follows as she approaches. “You two been having a good time, I hope?”

“I’m working,” Kai points out, despite the ample evidence to suggest otherwise. Mr. Lin raises a skeptical eyebrow, but Dr. Wang’s smile doesn’t flag.

“No reason that should stop you from enjoying yourself, though. You boys want anything? A beer, something to eat? I did say I’d pay —”

“We’re fine, Dr. Wang,” Eli says before she can continue. “How have you two been? Have you been enjoying yourselves?”

“But of course,” Dr. Wang says. She links an arm through Mr. Lin’s and he adopts the stoic expression of a man resigned to never understanding the ways of extroverts. “Lin da-ge has been showing me all around, and it’s quite fascinating. The variety of dragons on display, even within the same species. The level of adaptation in even third or fourth generations, the way cell membranes evolve to maximize water absorption even as the transport proteins become more adept at identifying and filtering out toxins — it makes you wonder if there might be some truth to the rumors, that we might see some trace of huolong —”

Behind his sketchbook, Kai makes a noise of disbelief.

Author Bio

Cynthia Zhang has fiction and non-fiction published in Lunch Ticket, Leading Edge, Orca Literary, and Coffin Bell. After the Dragons is her first novel.

| Author Twitter | https://twitter.com/cz_writes |