Unless you have self-published exclusively, rejection is a universal experience for authors. It’s not fun. It can hurt when you thought you’d found the perfect home for a story that’s been polished to within an inch of its literary life.

I’m sympathetic up to a point. Yes, I cried when I received my first rejection many years ago and I’ll allow you that. One good cry. Then it’s time to suck it up, buttercup, and make that which did not kill you help you become a better author. I have a box full of rejection letters from the bad old years when everything was done on paper and through snail mail, everything from the generic This does not meet our needs at this time, to specific reasons for rejection, (too long, not the right characters, not the right market) to my favorite from an agent: I’m so sorry. I love your story but I can’t take any new clients.

Rejections shouldn’t be seen as a failures, but as a chance to learn, adjust, and try again. So from the viewpoint of the acquisitions editor, let’s take a look at some types of rejections and some of the things you should and shouldn’t be doing when you receive them.

1. The generic rejection – Your submission does not meet our needs at this time.

This is by far the most frustrating type since it doesn’t give us concrete feedback. Our initial reaction as authors tends to be: They hated it. My writing sucks. I should crawl into the blanket fort and never come out. Crawl into the fort if you must, but don’t give up. Please remember that this type of rejection usually happens because the acquisitions editor/minions/elves are too busy to give authors specific feedback. They have a slush pile threatening to crush them and are struggling just to get responses out.

Some possible reasons your work was rejected? The magazine/journal/publisher has received ten stories about miraculous sea slugs in the past month. Yours was the eleventh. You may simply have written something too similar to stories they already have in the pipeline. The publisher is actively looking for a different type of story right now. They really weren’t the right market for your work. The editor reading your story didn’t connect with it. (We’re human. Fiction reading is subjective. This happens.) Your story wasn’t ready to be submitted yet.

Please keep that last one in mind – you may need some serious rewrites to make your story stronger. If you’re getting nothing but rejections, get some feedback.

2. The rejection with a reason – We enjoyed your story about zombie kittens from space, but we struggled with the horrible cuteness.

If a publisher gives you specific feedback, don’t rail and rant about how your work is misunderstood. Take a step back and process the feedback. Ask for objective opinions about the feedback. If you feel the story wasn’t right for that market, keep looking. Try again. But please keep in mind that the story may have issues that should be fixed.

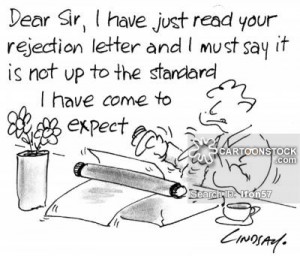

Whatever you do, please don’t respond to this type of rejection with something hurt, snarky, or angry. You shouldn’t be responding at all to rejections. Move along. Nothing to see here. But responding with piss and vinegar is unprofessional and the publisher is liable to remember that when they otherwise wouldn’t have remembered a story they didn’t want. Please, please be professional when receiving rejections.

3. The revise and resub – We enjoyed your story and would love to see the middle part with the confusing talking tribe of iguanas rewritten and resubmitted to us.

This isn’t really a rejection, folks. You need to take a hard look at your story and see if the suggested changes are ones you’re willing to make. Maybe write part of the story from the POV of the iguana librarian. Whatever it takes – this is a publisher who wants your work. They have shown interest and a willingness to work with you. If you’re serious about working with them, you’re going to sit your writer butt down, do the revisions, and resubmit in a professional, timely manner.

Bottom line? When you’re an author, rejections are part of your job. Don’t take them personally. Handle them professionally. Concede that you’re not an omniscient deity of writing and that we all have work to do.

Take pride in your rejections. An author who has no rejections is an author who isn’t submitting work.