Nearly 50 years since man first walked on the moon, the human race is once more pushing forward with attempts to land on the Earth’s satellite. This year alone, China has landed a robotic spacecraft on the far side of the moon, while India is close to landing a lunar vehicle, and Israel continues its mission to touch down on the surface, despite the crash of its recent venture. NASA meanwhile has announced it wants to send astronauts to the moon’s south pole by 2024.

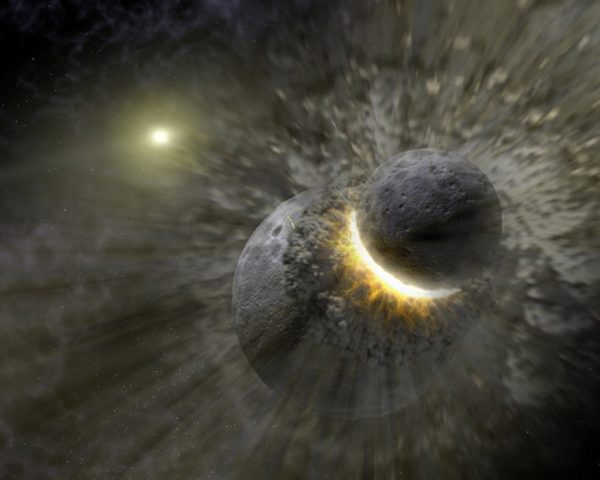

But while these missions seek to further our knowledge of the moon, we are still working to answer a fundamental question about it: how did it end up where it is?

On July 21, 1969, the Apollo 11 crew installed the first set of mirrors to reflect lasers targeted at the moon from Earth. The subsequent experiments carried out using these arrays have helped scientists to work out the distance between the Earth and moon for the past 50 years. We now know that the moon’s orbit has been getting larger by 3.8 cm per year — it is moving away from the Earth.

This distance, and the use of moon rocks to date the moon’s formation to to 4.51 billion years ago, are the basis for the giant impact hypothesis (the theory that the moon formed from debris after a collision early in Earth’s history). But if we assume that lunar recession has always been 3.8 cm/year, we have to go back 13 billion years to find a time when the Earth and moon were close together (for the moon to form). This is much too long ago — but the mismatch is not surprising, and it might be explained by the world’s ancient continents and tides.